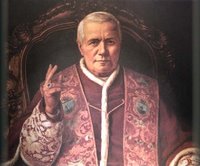

Pope Saint Pius X: Prophet of the Great War

by Dr. Peter E. Chojnowski, Ph.D.

by Dr. Peter E. Chojnowski, Ph.D.Pope St. Pius X, Giuseppe Melchior Sarto, stopped before the Lourdes grotto during his walk in the Vatican gardens in the spring of the year 1914. He turned to Monsignor Bressan, his confessor, and said, “I am sorry for the next Pope. I will not live to see it, but it is, alas, true that the religio depopulata is coming very soon. Religio depopulata.” The term “depopulated religion,” refers to the prophecy coming from the Irish Saint Malachy, and was to be applied to the reign of the successor on the Throne of St. Peter of Pius X himself. That St. Pius X could foresee the depopulation of Europe, especially in so far as that tragedy would affect the Catholic Church is truly one of the most salient features of the relationship between this pope and World War I (1914-1918). Many geo-political strategists and high-level observers could clearly envision some kind of altercation between two or more of the six Great Powers of Europe (i.e., Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Germany), no one foresaw the downfall of traditional Christian civilization, except for Pope St. Pius X. Even his own Secretary of State and intimate confidant, the Anglo-Spanish Cardinal Merry del Val, was at a loss to explain the Pope’s insistence that what he foresaw was not just war and blood, but the loss of the Common European Home; a loss which spelt travail for the Catholic Church and misery and loss for the preponderance of humanity.

A very similar situation, involving the Pope’s insight into a future geo-political happening, occurred during his audience with the future Austrian empress Zita in the summer of 1911. Princess Zita of the Franco-Italian royal house of Bourbon-Parma had just become engaged to the future heir to the Austrian imperial throne, Archduke Charles. Charles, in 1911, was second in line to the throne of his great-uncle Franz Josef who had reigned over the multi-national Imperium of Austria since 1848. The Pope, who along with Cardinal Merry del Val was a great supporter of the Habsburg European tradition, congratulated the Princess on her upcoming nuptials. At the end of a conversation which began with, “I am very happy with this marriage and I expect much from it for the future….Charles is a gift from Heaven for what Austria has done for the Church,” the Pope seemed wander in his thought when he referred to Zita’s future husband as the heir to the throne. When the young princess pointed out gently that her future husband was not the direct heir to the throne, first came his uncle the fated Franz Ferdinand, St. Pius X looked serious and insisted that Charles would soon be emperor. When she assured that Franz Ferdinand would certainly not abdicate on account of the fact that he was in the prime of life, the Pope looked troubled and ponderously said in a low voice, “If it is an abdication…I don’t know.”

That Pope St. Pius X should have precise presentiments concerning the two great events of the year 1914, years before those events actually in fact occurred, is simply uncanny and a manifestation of his intimacy with the Divine and his paternal concern for the daily lives of the European faithful. What these insights also reveal is the Pope’s clear appreciation of the primary European fact of his time, that Habsburg Austria was the cornerstone of Europe. In order to move the building, one had to dig up and remove the stone. World War I or the Great War was simply the uprooting of this stone. It was a war in which the political heart of Catholic Christendom was destroyed, apparently for good.

It is our thesis, that Austria was the reason for the Great War and that the most tangible outcome of the conflict was the break up of the Empire. Moreover, in later articles about the popes and their relationship to the Great Conflict, I will attempt to show how the fate of Austria had much to do with her attachment to the Papacy and how, in the most critical years of 1917-1918, Austria’s policy was in full accord with the objectives of Pope Benedict XV. That the failure of Austria-Hungary marked the exclusion of the voice of the popes from the councils of modern Europe, simply verifies the fact that, historically speaking, the prestige and influence of the altar and the throne have waxed and waned together.

A) Europe Pre-1914: The Proud Tower

When we look at the Europe of 1914, we are forced to admit one stark fact, it worked. By this, I mean that there existed a society, pillared by the same institutions that had bolstered it for more than a millennia (e.g., the rural village, the Church, the royal dynasties, the transnational aristocracies). This society was confident in itself, witness the European colonization of the world by this year. Its birth rates were very high; its kings were venerated and, even, loved. Industry, even in agrarian Russia, was expanding at a rate unknown in prior human history.

Why, in a world in which lights were finally going on, did they so suddenly go off? I am, of course, referring here to that famous statement by Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary in 1914 and, ironically, one of the men most responsible for the initiation of the bloody conflict, in which he commented upon the lights of Whitehall gradually being extinguished in the evening in August, 1914 when the British Empire and the German Empire went to war. “The lights are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

How can it be that the lights of the “Proud Tower,” as Barbara Tuchman entitled her book on pre-war Europe, went out? How can it be that a civilization that was better fed, better housed than any in the past, one of almost universal literacy --- it has been stated by some contemporary historians that there is more illiteracy in England today then there was in 1914 – a civilization in which standards of culture and parliamentary debate were so high that, in the 1890’s, in Berlin, there was even a black market for tickets to the public galleries of the German parliament, fall into oblivion due to self-slaughter?

Here, one can give historical facts and opinions concerning back-room diplomacy, troop levels, the status of railways, and geo-political posturing, however, these things alone were only manifestations of a more fundamental disorientation in European life, one which St. Pius X identified in his inaugural encyclical E Supremi Apostolatus on October 4, 1903. Here the Pope, speaking of his own day, says, “as might be expected we find extinguished among the majority of men all respect for the Eternal God, and no regard paid in the manifestations of public and private life to the Supreme Will.”

It is, perhaps, this thought that St Pius X had in mind when, on July 28, 1914, the Austrian Ambassador appeared before Pius X to inform him that the Empire had formally declared war upon the Kingdom of Serbia. During this meeting, the ambassador asked the Pope to bless the guns of the imperial and royal army of Austria and Hungary. To this Pius X replied, “Tell the Emperor that I can bless neither war, nor those who have desired war. I bless peace.” When the ambassador then followed up with a request for a personal blessing for the emperor, Franz Josef, the Pope stated, “I can only pray that God may pardon him. The Emperor should consider himself lucky not to receive the curse of the Vicar of Christ!”

What would have been the result of a papal blessing or a papal curse will never be known. What is clear, however, is that Pope St. Pius X realized what Emperor Franz Josef and most European generals appear to have been oblivious to, by the declaration of war against Serbia, the Habsburg monarch had unleashed the dogs of a long and murderous struggle that would level all that his dynasty had built over the course of some 700 years.

What exactly was the European situation, which gave St. Pius X such concern in 1914? How did the “short war” that everyone planned for, become the Great War, which very few, except the Pope, foresaw? To understand the European situation, in a general way, as it existed in 1914, one must focus one’s attention upon two other dates, that of the French Revolution of 1789 and that of the defeat of Napoleon and the restoration of the monarchical system in 1815. The French Revolution, a resurgence of enthusiasm for two antique forms of government, that of the republic and that of democracy, had terrified the broad mass of Europeans – and Americans – by its violence, its mindless toppling of ancient institutions, and its anti-clerical godlessness and hostility to everything Christian. This envy-driven political aberration would have been smothered in 1795, by a royalist mob in Paris who were reacting to the famine, incessant war, and anti-Catholicism of the regicidal First Republic, had not a young Corsican of Italian extraction, Napoleon Bonaparte, used grape-shot on the justice-seeking mob. This intervention saved the Republic, the heritage of the Revolution, and created the conditions necessary to spread that Revolutionary fervor throughout Europe.

This is exactly what happened when Napoleon Bonaparte institutionalized the Revolution in the First Empire. Making himself the crowned Jacobin, Napoleon tried to bring the Masonic uprising to all of Europe, from Lisbon to Moscow. He failed, after a generation of warfare due to Admiral Nelson’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar and his loss to the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. After the Congress of Vienna, the European Powers of Russia, Prussia (later to become the leader of the Second German Reich), Austria, Britain, and a monarchically rehabilitated France settled down into a somewhat tense, and relatively stable, political order of multi-national empires united by loyalty to a monarch and by the common desire to avoid another outbreak of the barbarism that was experienced during the French Revolution. For, approximately, 100 years this system was the European Order, even though democratic sentiments and uprisings, French republicanism, and Masonic sects were always acting as cancerous cells ready to kill the body of that Order.

In cameo, that was the Grand European Order that found itself entering the uncertainty of the 20th century. This tightly interlocked System had one particular concern and point of instability, the Ottoman Empire, Turkey, the “Sick Man of Europe.” The Osmanli Turks, a Turk-Tartar Islamic tribe out of Central Asia, in the early Renaissance began pushing the Byzantine Greeks out of Asia Minor and, finally, crossed into Europe, where they subjugated the Bulgars, Serbs, Greeks, and Bosnians. The high-water mark of the Islamic Turkish advance was in 1683 at the Gates of Vienna, where the Polish king Jan Sobieski stopped them. From then on there was a slow, agonizing withdrawal across the Balkan Peninsula until, in the 19th century, when the Ottoman’s lost sovereignty over Serbia, Greece, and Romania. During the Balkan War of 1912-1913, the Sultan’s European holdings were reduced to Eastern Thrace or the holdings that Turkey has to this very day. Due to the ethnic and religious mix of this area, and to the vulnerability of the small kingdoms, which, like maritime rocks, emerged with the recession of the Islamic flood, the chronic instability, which characterized the region, had to be “settled” by either the multinational empires of Austria or Russia.

B) Bosnia 1914: The Power Keg Ignites

In light of the power vacuum that was developing in this highly volatile region of Europe, the Berlin Conference of European Powers awarded the former Turkish Balkan provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Austria-Hungary in 1878. Bosnia and Herzegovina, with their capital in Sarajevo, were difficult provinces to govern since they were populated by an ethnic and religious mixture of Orthodox Serbs, who were allied in a very informal way with the Tsar’s empire in the East, Catholic Croats, who saw themselves as a cut about the Serbs on account of their ties to Vienna and Budapest, and finally, the Moslems, who were, actually, Croats who had apostatized to Islam when the region was under the Turkish yoke. It is very possible that this diverse district could have remained peaceful had it not been for the subversive actions of Bosnian Serbs who wished to join with the Serbian kingdom to the east. After the Balkan Wars from 1912-1913, Serbia doubled in size creating an almost irresistible draw for its Bosnian brothers. Here, again, such a situation need not have developed in the way in which it did, had not Serb military commanders and agents been training and arming Bosnian Serb youth in subversive and terrorist tactics from places safely across the border in Serbia proper. The historians writing on this period do not contest the fact of this activity on the part of the Serbs. As we shall see later, Pope St. Pius X himself did not contest the fact that the Serbs were acting to subvert Austria-Hungary, nor did he object to a “disciplining” of this renegade nation by the Habsburg Monarchy.

Habsburg Austria genuinely tried to advance the level of civilization and education of the Bosnians during the years before the war. After annexing the territory formally into the lands of the Monarchy in 1908, thereby obviating any Turkish or Serbian hope of regaining the territory (the territory had been controlled by the Serbs prior to the Turkish invasions), the Austrians built 4,000 kilometers of railway, 5,000 schools (on account of which half the population became literate by 1914), and roads and public buildings throughout the capital, Sarajevo. What was most important, however, from the point of view of the Great War, is that the heir to the imperial throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was actively working to establish a three-part division of the Habsburg domains, which would entail the setting up of a South Slav kingdom, reigned over by the Habsburg monarch, which would include the Croats and the Serbs in a unified political structure that would have as much autonomy as the Kingdom of Hungary. It is thought that this serious plan was much feared by those Serbian nationalists who could not brook the idea of Serbs being incorporated into a peaceful multi-ethnic state.

The situation came to a head in June 1914, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand (note this was prior to the days of the arm-chair “chicken-hawks”), as inspector of the army, was to view military maneuvers in Bosnia and then, with his wife the Duchess of Hohenburg, to make a courtesy visit to Sarajevo on June 28th, the day of a great Serbian holiday commemorating the battle for Kosovo. A thin military cordon was the only protection for the archduke’s car on the streets of Sarajevo. A Serb nationalist threw a bomb, however, it was not until the afternoon that the archduke and his wife, eager to visit an injured officer in their security detail, were gunned down by Serb nationalist Gavrilo Prinčip. Prinčip, after having failed to reach his target in the morning, found that due to a wrong turn down an unmaneuverable side street, the archduke’s car drove up to him, very slowly, and stopped. Prinčip fired several times before he was overpowered; the archduke and his wife were dead.

C) The Austrian Dilemma and the Papal Plea for Peace

On the night of June 28, 1914, the Pope was troubled with increasing apprehension. He called his Secretary of State. Merry del Val was frightened at the appearance of the Holy Father. Fear and worry were expressed in his drawn features, and the hand that he extended trembled. “Il guerone; the world war,” whispered Pius. “I know it is almost upon us.” “Oh, no, Holy Father,” “The political sky is cloudless. There is no danger; the diplomats are preparing to travel during vacation.” At hearing this, Pius X shook his head in disapproval, “We will not get through 1914 in peace,” moaned Pius, “Believe me, Eminence.” A rap at the door then interrupted the conversation. A dispatch was handed to Pope Pius. A glance at the sheet and his trembling hand dropped it. Excited, Merry del Val picked up the paper and read that the Austrian heir and his wife had been assassinated. Still not seeing the full implications of the event, the Cardinal tried to lessen the Holy Father’s anxiety by arguing that such an event would not devolve into continent-wide warfare. “O my Lord,” groaned the Pope. Then Pius dragged himself into his chapel and fell on his knees before the tabernacle.

What the Pope saw and what the Cardinal failed to see was that the precarious situation of entangled European alliances would not be able to simply overlook such a jarring event as the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. What the Pope seems to have realized at the time, was that Austria would be “required” to move in order to preserve her prestige in the assembly of nations and, yet, “unable” to move without mortgaging her security and sovereignty to her northern German neighbor. Even though no information has emerged concerning the specific nature of the Pope’s diplomatic activity from June 28, 1914 to August 4, 1914, the day on which the British issued an ultimatum that brought about war with Germany, it is clear from what is know that the Pope’s only desire was for the war not to happen at all. Even though he obviously appreciated the service that Austria had given to the Catholic Church against the Protestants to the North and the Schismatics to the East, from the contents of the interview between the Austrian ambassador and the Pope on July 28th, it is clear that he did not at all approve of Austria’s decision to go to war in order to resolve the Serbian problem. In fact, there have been some witnesses who say that the Pope wrote a letter to Emperor Franz Josef, imploring him to avoid a war. But, Cardinal Merry del Val himself said that he had no knowledge of this letter; there is no trace of it in the Austrian or Roman archives.

In July of 1914, the initiative lay with Germany. Since Austria’s 48 ½ divisions could not adequately deal with Serbia’s 11, especially if those 11 were supported by Russia’s 114 ½ infantry divisions and a French ally, Germany had to stand ready to support the Habsburgs if the path of war with Serbia was chosen. The German attitude towards war, the various opinions within the German leadership itself, and the sequence of events that precipitated the German invasion of Luxemburg and Belgium are not historical facts that can be easily discerned. The one German fact that has, perhaps, been the most misunderstood is that of the person of the German Emperor Wilhelm II. There seemed to be no overt hostility to Wilhelm II from St. Pius X. It is known that Wilhelm, from the House of Hohenzollern (whose senior branch is Catholic in religion), was not overtly hostile to the Catholic Church. He was the one who dismissed Otto von Bismark, the “Iron Chancellor” of the anti-Catholic Kulturkampf, he very much enjoyed trips to visit the pope in the Vatican, and was instrumental in allowing the Jesuits back into Germany after Bismark’s rule. The House of Hohenzollern, of course, allowed the Jesuits to exist in Prussia even after they were disbanded in the rest of Europe due to the Hohenzollern’s gratitude for a critical Jesuit intervention in the beginning of the 18th century, which allowed the Dukes of Prussia to receive a royal crown from the Holy Roman Emperor. As for Wilhelm’s responsibility for the outbreak of the world war, two German historians G.P. Gooch and Arthur Rosenberg investigated this question after the war. They were commissioned to do this investigation by the Socialist Republican government of Germany and, yet, these historians came up with a negative report. There is not evidence that Pius X thought the Kaiser to be primarily responsible either.

If the initiative lay with the Germans, what was their strategic thinking in the summer of 1914? In this regard, it is clear that the Germans were primarily concerned with the massive military progress of Russia in both the numbers in its standing army, its development of a Baltic naval fleet, and its building of railways across Poland to the German frontier. The German ambassador to the United States Kanitz, on July 30, 1914, indicated that German could not wait while Russia completed her plans to organize a standing army of 2.4 million men. With the French financed railway soon able to move these massive numbers to within 100 miles of Berlin, the imperial capital, the thinking of the German General Staff was that, if a war should come, it was preferable that it comes earlier rather than later. As German minister Riezler, basing his statement upon military intelligence at hand, stated, “After the completion of their [the Russian] strategic railroads in Poland our position will be untenable…The Entente knows that we are completely paralyzed.” What seems to confirm this pre-war mentality of the Germans are statements by two of the leading political and diplomatic figures in the Anglo-American world, Sir Edward Grey, Liberal British Foreign Secretary, and Colonel House, chief advisor to United States President Woodrow Wilson. According to Grey, in July 1914, “The truth is that whereas formerly the German government had aggressive intentions…they are now genuinely alarmed at the military preparations in Russia, the prospective increase in her military forces and particularly at the intended construction, at the insistence of the French government and with French money, of strategic railways to converge on the German frontier…Germany was not afraid, because she believes her army to be invulnerable but she was afraid that in a few years hence she might be afraid…Germany was afraid of the future.” Colonel House confirms this assessment in a letter he wrote to Wilson prior to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, “Whenever England consents, France and Russia will close in on Germany and Austria.”

D) The Summer Agony of the Pope and of Christian Europe

In a farewell audience on May 30, 1914, Dr. Chaves, the Brazilian ambassador who had been called home by his government, indicated to Pope St. Pius X that he had no misgivings regarding world events. In the course of their conversation, however, the Pope said, “Are you happy, Ambassador that you can return to Brazil? You will not be a witness of the war.” “Does your Holiness mean the Balkan strife?” “No, no, the Balkan trouble is but the beginning of a world conflagration which I cannot prevent.” We have seen this uncanny prophetic insight before in Pius X in the months prior to the outbreak of the Great War, what we have not seen as of yet is this understanding that he as Sovereign Pontiff was powerless, on the geo-political stage, to halt the conflict by any kind of natural means. “In ancient times the Pope with a word might have stayed the slaughter, but now I am powerless.”

Pope St. Pius X’s words were the same to a private consistory on May 25, 1914, when he said to the assembled cardinals, “More than ever does the world sigh for freedom. And yet we see how nation rises against nation, race against race, and we know how hate develops into terrible war.” Also, days before, the Pope said, “The tragedy which is coming is one which I am powerless to help men escape and which I shall not be able to halt. “I have the highest ministry of peace, and if I cannot protect the safety of so many young lives, who can – who will?” At this consistory in which his successor Giacomo della Chiesa (Pope Benedict XV) was given the red hat, the Pope was pessimistic about the chances of men of good will to avert the catastrophe to come, “unless at the same time an attempt is made to establish in the hearts of men the laws of peace and charity. The peace or the strife in civil society and the State depend less on those who govern than on the people themselves.” This pessimism regarding his ability to influence the cascading troubles inundating Europe should not be taken as a failure to appreciate the role of the Sovereign Pontiff in the world of human affairs. In fact, when we look at the Pope’s statements at the initiation of his pontificate concerning the pope’s role in political and social affairs, we can more perfectly understand his profound disappointment at being unable to affect the European situation in any way. In the first consistory of his pontificate, on Nov. 9, 1903, Pope St. Pius X emphasized the pope’s role as supreme teacher of the Moral Law and his right and duty to play an integral part in the politics of the world. Here he stated that, “It is Our program to renew all in Christ; Christ is truth, and we shall make it our first duty to preach and explain the truth in simple language that it may penetrate the souls of all and imprint itself upon their lives and conduct….We are convinced that many will resent Our intention of taking an active part in world politics, but any impartial observer will realize that the Pope, to whom the supreme office of teacher has been entrusted by God, cannot remain indifferent to political affairs or separate them from the concerns of Faith and Morals. And as the head and leader of the Church, a society of human beings, the Pope must naturally come into contact with the earthly governors of those human beings….One of the primary duties of the Apostolic Office is to disprove and condemn erroneous doctrines and to oppose civil laws which were in conflict with the Law of God and so to preserve humanity from bringing about its own destruction [emphasis added].

Simultaneous with his diplomatic efforts to avoid war, Pope Pius began to organize a Eucharistic Congress that was to meet in Lourdes from July 22-26, 1914. The Pope clearly believed that the only solution was for the faithful, in prayer, to avail themselves of the mercy of the Divine Love and the motherly solicitude of Our Lady. “We must pray. Only heaven can help --- God and the holy Virgin.” From a purely natural level, it is heart-rending to read of the child-like trust that the Pope placed in Our Lord and His Holy Mother, especially when we see his hopeful statements retrospectively from the perspective of the catastrophe of the Great War. In fact his recorded statement, “We must pray. The whole world must pray…The Lord and His Mother can avert the visitation; I want a Eucharistic Congress to be held in Lourdes. Perhaps --,” can only really be appreciated without maudlin pity, if we view this hope through the eyes of faith and with Our Lady’s apparition at Fatima in mind. I would venture to say that Our Lady’s appearance, message and miracle at Fatima are in direct response to the Pope’s prayerful petition.

The Eucharistic Congress itself was a great event, bringing together peoples from throughout the world all united in mind and prayer. There were lectures, conferences, and liturgical ceremonies. Every night there were great bonfires. All was ended with a singing of great Eucharistic hymn of praise written by St. Thomas Aquinas, the Tantum Ergo. Within days, the guns of war were heard on the frontiers. God would answer the prayers of the faithful, but in His time and in His way.

In one of the last days in July of that fateful year, Cardinal di Belmonte, Papal Delegate to the Congress, returned to Rome and told the Holy Father that, despite the rising tide of national hatreds, there was no doubt that that Pope himself was greatly loved in every land: each time the name of Pius was mentioned great enthusiasm had been shown by the crowds gathered at Lourdes. The Pope had proved himself to be what the popes were supposed to be on account of their sacred and exalted office, Father of all Christendom – a Christendom that would soon lose its claim to a visible presence in the world of men.

E) The August Passion

On July 29, 1914, only 3 days after the end of the Eucharistic Congress and one day after the declaration of war against Serbia by Austria, the Russians ordered a partial mobilization of their armed forces. This is exactly the action that threatened to find a reaction from Germany. Germany was committed to a strategic plan named after General von Schlieffen, in which mobilization by either Russia or France would be met with an immediate invasion of France and a declaration of war and, later, an eastern invasion of Russia. In order to avoid the vice of encirclement by the Entente Powers, Germany believed that she must first knock France out of the war, before turning on a slowly mobilizing Russia. Even though Emperor Nicholas II of Russia assured the Germans that this partial mobilization did not mean war, the Germans stated that, nevertheless, they would be forced to mobilize themselves. The Pan-Slavic foreign minister Sazonov and the Chief of the General Staff Nikolai Yanuskyevich were committed to full mobilization and finally cajoled Nicholas II to agree to it on July 30. Here Nicholas’ cousin, the German emperor appealed to the Russian emperor to halt mobilization or it would mean war. These appeals to the Russian monarch were futile on account of the adamant insistence upon mobilization by General Yanuskyevich. After the war, Yanuskevich testified to acting as he did due to Pan-Slavic principles (the belief that all the Slavic peoples should be joined together under Russian hegemony), sentiments that he knew the emperor, being of mixed Danish and German origin would not share. So, on the last days of July 1914, Yanushkyevich resolved to “smash my telephone and generally adopt measures which will prevent anyone [i.e., the Tsar] from finding me for the purpose of giving contrary orders which would again stop our mobilization.” If Russia continued to mobilize, the Germans insisted they had no option but to do the same. That meant, on account of the offensive/defensive von Schieffen Plan, the invasion of Belgium and France. “War by timetable” between the four continental powers commenced the moment Russia decided upon full mobilization. To put it in a straightforward way, World War I began when Yanushkyevitch, with the aid of Russian Minister of War Sukhomlinov, transformed the Austro-Serb armed conflict into a world war preparing, therefore, for the coming of Communism and the “spreading of the errors of Russia” throughout the world.

The time of religio depopulata was fast approaching. On August 2nd, the Pope directed a sharply worded warning to the whole world and asked all to pray. Pius was wearing away from grief and worry. He could only drag himself to his audiences, but he had no strength to speak to huge crowds. “My children, my children. I suffer for all who die on the battlefield.” “Oh, this war --- I feel this war is my death. But I gladly offer my life for my children and for world peace.” During the first half of August, Pius X blessed groups of pilgrims in silence, but gave no public addresses. He slept less than usual. His health, however, prior to the last five days of his life seemed fairly good and neither his doctors nor his sisters, who helped to take care of him when he took up residence at the Vatican, were unduly concerned about his health.

After giving his last audience on the Feast of the Assumption, to a group of Americans – as he had entertained at the first audience of his pontificate in 1903 – he came down with a high fever on August 19th and was completely prostrate. Now he realized the seriousness of his condition and is recorded to have said, “May God’s will be done. I think it is the end. Perhaps He in His goodness wishes to spare me the horrors Europe will undergo.” That evening, Cardinal Merry del Val, when hearing from the doctors that the Pope was threatened with pneumonia, despaired of his recovery, “He has suffered too much from the strain of public events to offer prolonged resistance to serious illness.” According to his doctor Machiafava, Pius X said, “I am offering my miserable life as a holocaust to prevent the massacre of so many of my children.” Then, in the early hours of August 20th, with the bells tolling throughout Rome indicating the Pope’s final agony, he spoke his last words, which, according to the most recent scholarship, were an act of trust. In his own Venetian dialect he said, “Gesu, Giuseppe e Maria, vi dono il cuore de l’anima mia! (Jesus, Joseph, and Mary, I give to you the heart of my soul) The Catholic, the peasant, the pontiff, and the lover of the souls of men were one at the moment of perfect and utter self-surrender.

<< Home